Art Artwork and Painting

Art Artwork and Painting

Is Graffiti Art?

You can travel almost anywhere in the world, and you will probably see graffiti. Although graffiti art is usually more common in big cities, the reality is that it can occur in almost any community, big or small.

The problem with graffiti art is the question of whether it’s really art, or just plain vandalism. This isn’t always an easy question to answer, simply because there are so many different types of graffiti. Some is simply a monochrome collection of letters, known as a tag, with little artistic merit. Because it’s quick to produce and small, it is one of the most widespread and prevalent forms of graffiti.

Although tagging is the most common type of graffiti, there are bigger, more accomplished examples that appear on larger spaces, such as walls. These are often multicolored and complex in design, and so start to push the boundary of whether they should really be defined as graffiti art.

If it wasn’t for the fact that most graffiti is placed on private property without the owner’s permission, then it might be more recognized as a legitimate form of art. Most graffiti art, however, is only an annoyance to the property owner, who is more likely to paint over it or remove it than applaud its artistic merit.

Many solutions have been put into practice around the world, with varying degrees of success. Paints have been developed that basically cause graffiti paint to dissolve when applied, or else make it quick and easy to remove. Community groups and government departments coordinate graffiti removal teams.

In some places you can’t buy spray paint unless you’re over 18. Cans of spray paint are locked away in display cases. In a nearby area the local council employs someone to go around and repaint any fences defaced by graffiti. A friend of mine has had his fence repainted 7 times at least, and it took him a while to find out why it was happening! Certainly the amount of graffiti in my local area has dropped substantially in the last year or two, so it appears these methods are working to a great extent.

But is removing the graffiti doing a disservice to the artistic community? Maybe if some of the people behind the graffiti art were taken in hand and trained, they could use their artistic skills in more productive ways. It hardly makes sense to encourage these artists to deface public property, and so commit a crime. But perhaps there are other ways to cooperate with the graffiti artists rather than just opposing them. Graffiti artists can create sanctioned murals for private property owners and get paid for it.

Maybe we need to start at a very basic level, and find a way to encourage the creation of graffiti art on paper or canvas, rather than walls. After all, who would remember Monet or Picasso if they’d created their masterpieces on walls, only to have them painted over the next day? Finding a solution to such a complex situation is never going to be easy, but as more graffiti art is being recognized in galleries around the world, we do need to try.

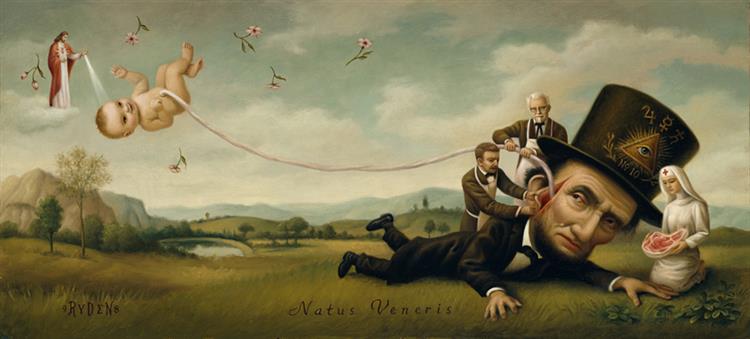

The Artwork of Mark Ryden

Mark Ryden’s artwork has been described as captivating and disconcerting, mysterious and enthralling, unsettling, mystical, cuddly and frightening all at once.

Ryden has been referred to as the king of the Pop Surrealism movement. Mixing joyful child-like imagery with disconcerting pieces of body parts or bizarre sights in nature, forming a strange mixture of children’s book images and meat or blood. Moved by alchemy, metaphysics, science, and philosophy and attracted to ancient cryptic symbols and mystical imagery, Mark Ryden produces incredible storybook artworks which are stunning yet disturbing.

Ryden’s artwork mixes saccharine-sweet, cartoon-like characters with a detailed fullness and a eerie combination of numerology, little girls, meat, Catholic and Buddhist symbolism, and carnivalesque Americana. fascinated by things that take you back to memories from childhood, Mark Ryden frequently incorporates toys, as well as scenes of bunnies, children, clowns, and ice cream trucks, which just happen to be united with skulls and porterhouse steaks.

Ranging from big highly-polished oil paintings to small black-and-white works on paper, Mark Ryden exploded onto the art scene in the 1990s as both pop art illustrator and fine art painter. His artwork has gained increased popularity due to publications such as Juxtapoz, which features his art regularly, and to his artwork on many album covers such as Michael Jackson’s “Dangerous,” Red Hot Chili Peppers “One Hot Minute,” Scarling’s “Sweet Heart Dealer” as well as covers for Ringo Starr and Jack Off Jill. Ryden’s art can also be seen on the dustjacket of Stephen King’s novels “Desperation” and “The Regulators.”

Many people have become fans after Chris Garver did a replica of Ryden’s print “Rose” on Miami Ink and his work is now highly sought after for tattoos. However, it takes a highly talented artist to be able to recreate his distinctive masterpieces.

“Rose”, a gothic girl crying tears of blood is the most popular of his paintings to be translated to skin, though many others have also made the leap including “Fountain,” a painting of a girl holding her head while blood spurts from her neck, “Nurse Sue,” and “Dog Named Jesus.”

“I find it so much easier to be creatively free at night. Daytime is for sleeping. Nighttime is the best time for making art. The later at night it gets the further into another world you go.” – Mark Ryden

A Review of Michael Baxandall’s Painting and Experience in 15th Century Italy

Baxandall’s Painting and Experience in Fifteenth-Century Italy: A Primer in the Social History of Pictorial Style was first published in 1972. Although relatively short it has subsequently been published in numerous languages, most recently Chinese, with a second edition published in 1988. Since publication it has been described in such favourable terms as being ‘intelligent, persuasive, interesting, and lucidly argued’ to ‘concise and tightly written, and being found to ‘present new and important material’. It may have been published as a book with three chapters. In reality it is three books in one.

Baxandall brings together many strands of previous art historical methodology and moves them forward in Painting and Experience. As the history of art was emerging discipline Art came to be seen as the embodiment of a distinctive expression of particular societies and civilisations. The pioneer of this was Johann Joachim Winckelmann in his History of the Art of Antiquity (1764). Baxandall is certainly not the first to consider how an audience views a painting. He is not the first to discuss patronage either given Haskell published his Patrons and Painters in 1963. Lacan created the concept of the ‘gaze’ and Gombrich the idea of ‘the beholder’s share’ before Baxandall published Painting and Experience. Baxandall does describe chapter two of Painting and Experience as ‘Gombrichian’. Baxandall spent time with anthropologists and their exploration into culture, particularly that of Herskovits’ and his ideas on cognitive style. Baxandall’s approach focuses on how the style of paintings is influenced by patrons who commission and view paintings. The patron’s view is culturally constructed. For Baxandall ‘a fifteenth-century painting is the deposit of a social relationship’. This quote is the opening sentence of the first chapter in Painting and Experience; ‘Conditions of Trade’.

Baxandall’s first chapter in Painting and Experience on the ‘Conditions of Trade’ seeks to explain that the change in style within paintings seen over the course of the fifteenth century is identified in the content of contracts and letters between patron and painter. Further to this that the development of pictorial style is the result of a symbiotic relationship between artist and patron. However, this relationship is governed by ‘institutions and conventions – commercial, religious, perceptual, in the widest sense social… [that] influenced the forms of what they together made’. Baxandall claims his approach to the study of patron and painter was in no way impacted by Francis Haskell’s seminal 1963 book, Patrons and Painters nor by D.S. Chambers’ Patrons and Artists in the Italian Renaissance.

Baxandall’s main evidence to support the development of pictorial style is demonstrated by the change in the emphasis to the skill of the artist over the materials to be used in the production of a painting as shown by the terms of the contract between artist and client. This is the unique element that Baxandall introduces to the examination of contracts between patron and painter and one that had not previously been explored. He supports this argument by referring to some contracts where the terms show how patrons demonstrated the eminent position of skill over materials. In the 1485 contract between Ghirlandaio and Giovanni Tornabuoni, the specifics of the contract stated that the background was to include ‘figures, building, castles, cities.’ In earlier contracts the background would be gilding; thus Tornabuoni is ensuring that there is an ‘expenditure of labour, if not skill’ in this commission.

Baxandall states that ‘It would be futile to account for this sort of development simply within the history of art’. Indeed to ensure his argument is placed in the domain of social and cultural history Baxandall refers to the role, availability and perception of gold in fifteenth-century Italy. Baxandall uses the story of the Sienese ambassador’s humiliation at King Alfonso’s court in Naples over his elaborate dress as an example of how such conspicuous consumption was disparaged. He cites the need for ‘old money’ to be able to differentiate itself from ‘new money’ and the rise of humanism as reasons for the move towards buying skill as a valuable asset to display.

Herein lies the main difficulty with Baxandall’s approach to identifying the influence of society on pictorial style through the conditions of trade. How would the viewer of a painting recognise that skill had been purchased? Baxandall asks this question himself and states that there would be no record of it within the contract. It was not the usual practice at that time for views on paintings to be recorded as they are today consequently there is little evidence of this. Additionally, there is nothing in the contract that Baxandall presents us with that mentions the actual aesthetic of the painting; expressions of the characters; the iconography, proportions or colours to be used.

Joseph Manca was particularly critical of this chapter in stating that ‘Baxandall’s early discussion of contracts has us imagining a dependent artist who is ever-ready to echo the sentiments of his patrons or public’. We know this is not true. Bellini refused to paint for Isabella d’Este because he was not comfortable painting to her design. Even though Perugino accepted the commission from Isabella he ‘found the theme little suited to his art’.

Baxandall makes no accommodation for the rising agency of the artist and the materials to which they have access as influences on style. Andrea Mantegna’s style was heavily influenced by his visits to Rome where he saw many discoveries from ancient Rome, often taking them back to Mantua. Furthermore, Baxandall does not examine the training that artists received during fifteenth-century Italy to ascertain whether this could be an explanation of their style or how it developed. All of the painters Baxandall refers to were part of workshops and were trained by a master. As such there would be a style that would emanate from these workshops. It was recognised that pupils of Squarcino, including Mantegna and Marco Zoppo, ‘came to have common features in their art’. In 1996 he said ‘I didn’t like the first chapter of Painting and Experience. I had done it quickly because something was needed, and it seemed to me a bit crass’.

The central chapter of Painting and Experience is about the ‘ whole notion of the cognitive style in the second chapter, which to me is the most important chapter, [and] is straight from anthropology. This chapter is Baxandall’s idea of the ‘Period Eye’.

Baxandall opens the ‘period eye’ by stating that the physiological way in which we all see is the same, but at the point of interpretation the ‘human equipment for visual perception ceases to be uniform, from one man to the next’. In simple terms, the ‘period eye’ is the social acts and cultural practices that shape visual forms within a given culture. Furthermore, these experiences are both shaped by and representative of that culture. As a consequence of this patrons created a brief for painters that embodied these culturally significant representations. The painter then delivers paintings in such a way as to satisfy the patron’s requirements including these culturally significant items within their paintings. Baxandall’s chapter on the ‘period eye’ is a tool for us to use so that we, the twenty-first-century viewer can view fifteenth-century Italian paintings through the same lens as a fifteenth-century Italian businessman. The ‘period eye’ is an innovative concept that embodies a synchronic approach to the understanding of art production. It moves away from the cause and effect ideas that were taking hold of art historical enquiry in the early 1970s. But how was it constructed?

Baxandall’s asserted that many of the skills viewers acquired when observing paintings were acquired outside the realm of looking at paintings. This is where he examines the economic machinations of Florence’s mercantile community and notes that barrel gauging, the rule of three, arithmetic and mathematics were skills much required by merchants, and these gave them a more sophisticated visual apparatus with which to view paintings. Baxandall believes that the ability to do such things as gauge volumes at a glance enabled the mercantile classes to perceive geometric shapes in paintings and understand their size and proportion within the painting relative to the other objects contained within it.

Baxandall also refers to dance and gesture as further examples from the social practices of the day that enabled viewers of paintings to understand what was happening within them. Baxandall asserts that the widespread engagement in the Bassa Danza enabled the courtly and mercantile classes to see and understand, movement within paintings.

One of the major questions posed by the application of the ‘period eye’ is evidence that it has been applied correctly. Using Baxandall’s approach how did you know if you got it right – is it ever possible for a twenty-first century Englishman to view a painting as a fifteenth-century businessman even with an insight into Italian Renaissance society and culture? The evidence that Baxandall relies on to demonstrate that the pictorial style of fifteenth-century Italian painting developed seems extremely tenuous. Goldman, in his review of Painting and Experience, challenges Baxandall on this by saying that there is no evidence that modern-day building contractors and carpenters are especially skilled at identifying the compositional elements they see in a Mondrian. Likewise, the argument put forward by Goldman can be extrapolated into the other examples that Baxandall uses such as dance being reflective of movement in paintings. An example is Botticelli’s ‘Pallas and the Centaur’ where Baxandall describes it is a ballo in due which Hermeren, in his review, says this is not a useful piece of evidence as most paintings can be described in that way.

The final chapter turns attention to primary sources as Baxandall refers to Cristoforo Landino’s writings on the descriptors used during the fifteenth-century in Italy for various styles seen in paintings. The reason for doing so is that Baxandall claims this is the method through which the twenty-first-century viewer can interpret documents about paintings that were written during the fifteenth-century by those not skilled in describing paintings. With this tool, it is then possible to gain a clearer understanding of what was meant by terms such as aria and dolce. Baxandall uses this approach to interpret the meaning to the adjectives contained within the letter to the Duke of Milan from his agent within chapter one of Painting and Experience.

Although this chapter is detailed and provides a ‘meticulous analysis of Landino’s terminology of art’ Middledorf believes it does little to ‘throw any light on the style of Renaissance painting’. As it is always difficult for words to capture what a painting is conveying this chapter, although worthy, does not provide sufficient information that is of value to a contemporary viewer in entering the mindset of the fifteenth-century viewer. It is unlikely a patron used such language when commissioning paintings. It is also questionable whether this was the type of language that was used amongst artists themselves to discuss their styles and approaches. Of course, there is material from artists of that time that describe how paintings can best be delivered, but even these seem too abstract to be of practical value as per the example of Leonardo da Vinci writing on ‘prompto’.

On publication Painting and Experience received less attention that Baxandall’s Giotto and the Orators. ‘when that book came out many people didn’t like it for various reasons’. One of the main reasons was the belief that Baxandall was bringing back the Zeitgeist. This leads us to other problems identified in response to the question of what kind of Renaissance does Painting and Experience give us. It gives us a Renaissance that centres on Italy in the fifteenth century, on the elite within society as a group and men only. It is a group of people that represents a fraction of society. They do commission most of the paintings hung in public, but they are not the only viewers of it. The full congregation at Church would view these paintings, and they came from all walks of life. For this reason, Marxist social historians, such as T.J Clark, took issue with the book claiming that it was not a true social history as it focused only on the elite within society without ‘dealing with issues of class, ideology and power’.

Baxandall also rejects the idea that the individual influences pictorial style given each experience the world in a different way. He acknowledges that this is true but that the differences are insignificant. This is in stark contrast to ‘the Burkhardtian idea that individualism in the Renaissance changed subject matter (the expansion of portraiture, for example)’. Four years before the second edition of Painting and Experience Stephen Greenblatt published Renaissance Self-fashioning, a book devoted to the methods through which individuals created their public personas in the Renaissance.

There are additional problems raised by Baxandall’s method. The evidence that Baxandall relies on to support his theses is literary. For example, in addition to chapter three’s use of Landino’s writings in chapter two made much of the sermons as a source of information through which to build the ‘period eye’ and in chapter one all of the evidence exists within written contracts. This begs the question of how Baxandall’s approach is applied to a society in which the art survives, but the writing does not. For example, the Scythians of Central Asia, where scholars admit there is a lot that will not be understood of this ancient people because they had no written language. It appears that in this instance that Baxandall’s approach is impossible to adopt and herein we see another of its limitations.

Perhaps the most glaring omission in Painting and Experience is any reference to the role that the revival of classical art played in the creation of Renaissance paintings and their style. The Renaissance was the rebirth of antiquity. Burkhardt writes a chapter on the revival of antiquity in The Civilisation of the Renaissance in Italy. It must be argued that the revival of antiquity is a contribution to the pictorial style of fifteenth-century Italy.

Painting and Experience had its many supporters who viewed it has an important guide to bringing out the direct causal relationships between artistic and social change. It was met warmly and was influential in disciplines beyond just art history such as anthropology, sociology and history as well as being credited with the creation of the term ‘visual culture’. In 1981 Bourdieu and Desault dedicated a special issue of Actes de la recherché en sciences sociales to Baxandall.

Baxandalls’ analysis of the conditions of trade, despite some shortcomings, has not been without influence. Baxandall refers to money and the payment mechanism in this chapter saying that ‘money is very important for art history’. His focus on the economic aspect of the production of painting garnered favourable reactions from ‘those drawn to the notion of economic history as a shaper of culture’. In the field of sociology: ‘His interest in markets and patronage made him a natural point of reference for work in the production of culture perspective, such as Howard Becker’s (1982) Art Worlds’. However, Baxandall was very critical of this first chapter.

Andrew Randolph extends the idea of the ‘period eye’ to the ‘gendered eye’ in an exploration of how the period eye can be applied to women. Pierre Bourdieu creates the concept of the ‘social genesis of the eye’ which is the revision of his concept of ‘encoding/decoding’ after having encountered Painting and Experience which allowed Bourdieu to ‘place a proper emphasis on particular social activities which engage and train the individual’s cognitive apparatus’. Clifford Geertz was an anthropologist who was able to refine the early structuralist model in anthropology that had been created by Levi-Strauss by incorporating ideas from Painting and Experience. In the field of history of art, Svetlana Alpers applied aspects of Painting and Experience in her book on Dutch art, The Art of Describing and credited Baxandall with creating the term ‘visual culture’. For historians, Ludmilla Jordanova posits that the approach contained within Painting and Experience highlights to historians the importance of approaching visual materials with care and that it can assist in identifying the visual skills and habits, social structure and the distribution of wealth within a society.

Painting and Experience was described by Baxandall as ‘pretty lightweight and flighty’. It was not written for historians of art but was borne out of a series of lectures that Baxandall gave to history students. As we have seen it has had an exceptional impact not only in Renaissance studies and history of art but across many other disciplines too. It has spawned ideas of the ‘social eye’, the ‘gendered eye’ and even gone on to create new terminology in the form of ‘visual culture’. It is a book to be found on reading lists at many universities around the world today. Painting and Experience may have its problems but remains important because it highlights how interconnected life and art have truly become. What Baxandall tries to give us is a set of tools to rebuild the Quattrocentro lens for ourselves; not only through the ‘period eye’ but analyses of contracts between patrons and painters. Along with that and an understanding of the critical art historical terms of the time, Baxandall enables us to identify the social relationships out of which paintings were produced by analysing the visual skill set of the period. We are left wondering whether we have been able to do that. There are no empirical means of knowing whether we have successfully applied the ‘period eye’. We are in fact left to ‘rely on ingenious reconstructions and guesswork’. The visual skills Baxandall attributes to the mercantile classes he believes are derived from their business practices, such as gauging barrels, impacting their ability to appreciate better forms and volumes within paintings is nothing less than tenuous. Not only that but the approach is specific to a single period and has to be rebuilt each time it is applied to a different era. Baxandall’s approach allows for no concept of the agency of the artist, their training or in fact the importance of antiquity to fifteenth-century Italians.

The question remains as to whether it is possible to write a ‘social history of style’. Baxandall has tried to do so but his assumptions and extrapolations and the inability to prove success leave an approach that is too shaky to constitute a robust method.

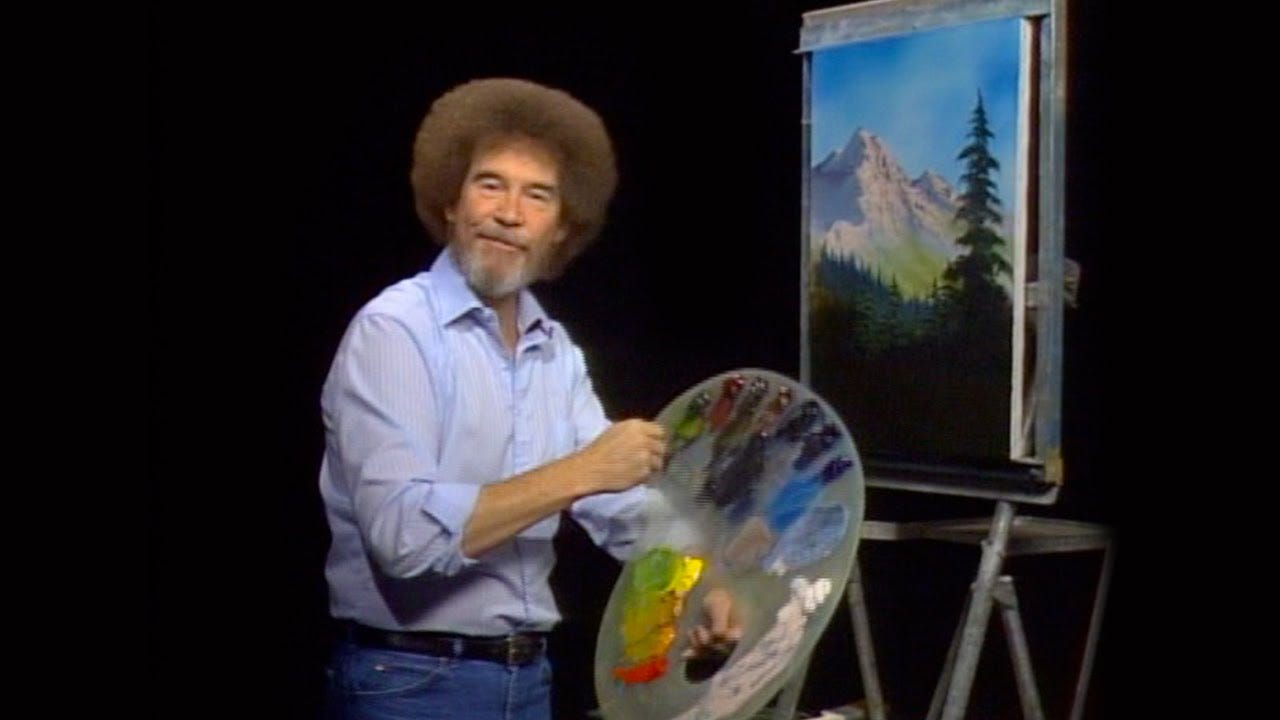

Bob Ross Oil Painting Technique – Frequently Asked Questions

The following is a list of frequently asked questions about the BOB ROSS Oil Painting Technique and some instruction about the use and care of the materials.

BLENDING:

This technique refers to the softening of hard edges and most visible brush strokes by blending the wet oil paint on the canvas with a clean, dry brush. In blending, an already painted area is brushed very lightly with criss-cross strokes or by gently tapping with the corner of the brush. This gives colors a soft and natural appearance. Not all oil paints are suitable for this technique – most are too soft and tend to smear. Only a thick, firm paint is suitable for this technique.

MARBLING:

To mix paints to a marbled effect, place the different colored paints on the mixing area of your palette and use your palette knife to pick up and fold the paints together, then pull flat. Streaks of each color should be visible in the mixture. Do not over mix.

THINNING PAINTS FOR ADDING HIGHLIGHTS:

When mixing paints for application over thicker paints already on the canvas, especially when adding highlight colors, thin the paint with LIQUID WHITE, LIQUID CLEAR or ODORLESS THINNER. The rule to remember here is that a thin paint will stick to a thicker paint.

CLEANING AND DRYING THE BRUSHES:

Painting with the wet on wet technique requires frequent and thorough cleaning of your brushes with paint thinner. An empty one pound coffee can is ideal to hold the thinner, or use any container approximately 5″ in diameter and at-least 6″ deep. Place a Bob Ross Screen in the bottom of the can and fill with odorless thinner approximately 1″ above the screen. Scrub the brushes bristles against the screen to remove paint sediments which will settle on the bottom of the can.

Dry your larger brushes by carefully squeezing them against the inside of the coffee can, then slapping the bristles against a brush beater rack mounted inside of a tall kitchen trash basket to remove the remainder of the thinner. Smaller brushes can be cleaned by wiping them with paper towel or a rag (I highly recommend using Viva paper towels because they are very absorbent). Do not return the brushes to their plastic bags after use, this will cause the bristles to become limp. Never clean your Bob Ross brushes with soap and water or detergent as this will destroy the natural strength of the bristles. Store your brushes with bristles up or lying flat.

APPLYING LIQUID WHITE:

Use the 2″ brush with long, firm vertical and horizontal strokes across the canvas. The coat of Liquid WHITE should be very, very thin and even. Apply just before you begin to paint. Do not allow the paint to dry before you begin.

PLACEMENT OF OIL COLORS ON THE PALETTE:

I suggest using a palette at least 16″x20″ in size. Try arranging the colors around the outer edge of your palette from light to dark. Leave the center of the palette for mixing your paints.

LOADING YOUR BRUSH:

To fully load the inside bristles of your brush first hold it perpendicular to the palette and work the bristles into the pile of paint. Then holding the brush at a 45 degree angle, drag the brush across your palette and away from the pile of paint. Flipping your brush from side to side will insure both sides will be loaded evenly.

(NOTE: When the bristles come to a chiseled or sharp flat edge, the brush is loaded correctly.)

For some strokes you may want the end of your brush to be rounded. To do this, stand the brush vertically on the palette. Firmly pull toward you working the brush in one direction. Lift off the palette with each stroke. This will tend to round off the end of the brush, paint with the rounded end up.

MIXING FOR HIGHLIGHTS:

Place the tip of your brush into the can of LIQUID WHITE, LIQUID CLEAR or ODORLESS THINNER allow only a small amount of medium to remain on the bristles. Load your brush by gently dragging it through the highlight colors, repeat as needed. Gently tap the bristles against the palette just enough to open up the bristles and loosen the paint.

LOADING THE PALETTE KNIFE:

With your palette knife, pull the mixture of paint in a thin layer down across the palette. Holding your knife in a straight upward position, pull the long working edge of your knife diagonally across the paint. This will create a roll of paint on your knife " Salah eddine Laouina artist painter ".

WHAT IF I HAVE NEVER PAINTED BEFORE?

There are no great mysteries to painting. You need only the desire, a few basic techniques and a little practice. lf you are new to this technique, I strongly suggest that you read the entire section on “TIPS AND TECHNIQUES” prior to starting your first painting. Consider each painting you create as a learning experience. Add your own special touch and ideas to each painting you do and your confidence as well as your ability will increase at an unbelievable rate.

WHAT PAINT SHOULD I USE?

The BOB ROSS technique of painting is dependent upon a special firm oil paint for the base colors. Colors that are used primarily for highlights (Yellows) are manufactured to a thinner consistency for easier mixing and application. The use of proper equipment helps assure the best possible results.

Liquid Clear is a particularly exciting ingredient for wet-on-wet painting. Like Liquid White/Black, it creates the necessary smooth and slippery surface. Additionally, Liquid Clear has the advantage of not diluting the intensity of other colors especially the darks which are so important in painting seascapes. Remember to apply Liquid Clear very sparingly! The tendency is to apply larger amounts than necessary because it is so difficult to see.

13 colors we use are listed below:

- Alizarin Crimson

- Sap Green, Bright Red

- Dark Sienna

- Pthalo Green

- Cadmium Yellow

- Titanium White,

- Pthalo Blue,

- Indian Yellow

- Van Dyke

- Brown

- Midnight Black

- Yellow Ochre

- Prussian Blue (*indicates colors that are transparent or semi-transparent and which may be used as under paints where transparency is required.)

HOW DO I MIX COLORS?

The mixing of colors can be one of the most rewarding and fun parts of painting, but may also be one of the most feared procedures. Devote some time to mixing various color combinations and become familiar with the basic color mixtures. Study the colors in nature and practice duplicating the colors you see around you each day. Within a very short time you will be so comfortable mixing colors that you will look forward to each painting as a new challenge.

SHOULD YOU USE JUST ANY ART PRODUCT FOR THIS METHOD OF PAINTING?

Possibly the #1 problem experienced by individuals when first attempting this technique and the major cause for disappointment revolves around the use of products designed for other styles of painting or materials not designed for artwork at all (i.e. house painting brushes, thin soupy paints, etc.).

All of the paintings for this technique were created using Bob Ross paints, brushes and palette knives. To achieve the best results from your efforts, I strongly recommend that you use only products designed specifically for use with the Bob Ross wet-on-wet technique.

HOW LONG WILL IT TAKE MY PAINTING TO DRY?

Drying time will vary depending on numerous factors such as heat, humidity, thickness of paint, painting surface, brand of paint used, mediums used with the paint, etc. Another factor is the individual colors used. Different colors have different drying times (i.e., normally Blue will dry very fast while colors like Red, White and Yellow are very slow drying). A good average time for an oil painting to dry, when painted in this technique, is approximately one week.

SHOULD I VARNISH MY PAINTINGS?

Varnishing a painting will protect it from the elements. It will also help to keep the colors more vibrant. lf you decide to varnish your painting, I suggested that you wait at least six months. It takes this long for an oil painting to be completely cured. Use a good quality, non-yellowing picture varnish spray. I personally spray my paintings after about 4 weeks and have not had any problems.

Comments

Post a Comment